Dark Matter and Trojan Horses

I have just finished reading Dan Hill’s 2012 essay Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary.

Hills describes himself as a ‘designer and urbanist’. The focus of this essay is largely on the practice of a more strategic approach to design as it pertains to product design, architecture and public infrastructure projects. However, there were some obvious areas of overlaps with strategy and how it is practiced in the communications industry.

A video of Hill summarising his thinking is below and worth a watch.

At the beginning of this video, he describes why he needs a vocabulary around the topics he is going to discuss. A vocabulary, he says is “about making things legible and helping us understand what is going on”. In other words, they provide the framework for shared understanding, giving people the means of discussing complex topics.

Roger Martin has also written recently on the need to install a ‘singular strategic language’ in organisations. Even when issues are instinctively and intuitively obvious, they can be difficult to address unless they have a common name and definition. In an industry obsessed with jargon, this was a timely reminder about basic communication and the value of well defined, consistent language.

Beyond this reminder, a number of conceptual pillars of Hill’s thesis stood out clearly as useful frames of reference or tools that could be applied to the discipline of communications planning and the practice of strategy within communications agencies.

Dealing with dark matter

Hill draws a parallel between the concept of dark matter and the way that companies operate. Drawn from the field of theoretical physics, the concept of dark matter suggests that there is an elemental force which accounts for 83% of all matter in the universe, whilst remaining entirely undetectable. Explaining this theory more, Hill says:

“The only way dark matter can be perceived is by implication, through its effect on other things…. with a product, service or artefact, the user is rarely aware of the organisational context that produced it, yet the outcome is directly affected by it. A particular BMW car is an outcome of the company’s corporate culture, the legislative frameworks it works within, the business models it creates, the wider cultural habits it senses and shapes, the trade relationships, the logistics and supply networks… the design philosophies that underpin it’s performance, the path dependencies in the history of northern Europe… This is all dark matter; the car is the matter it produces" (Hill, 2012, p. 82)

Strategic design, Hill contends, seeks to address “the missing mass” head on as this is “key to unlocking a better solution… that sticks at the initial contact point and then ripples out to produce systemic change” (Hill, p.83).

Framing the make up of a project or task in this way helps one to understand why good ideas sometime fail to land or don’t bring about meaningful changes in behaviour or approach.

It is also instructive: it quantifies something we already instinctively feel, but don’t always acknowledge. How much emphasis do we place on this 83%? Do we spend 83% of our time thinking about how we can sell our ideas, especially when the ideas are big, challenging or innovative?

This insight encourages a worldview where the origination of answers to briefs is positioned as a smaller component of the over overall task at hand, relative to the requirement to navigate and influence the systems and processes that live around the briefs and projects we work on. It crystallises the need for Strategists to learn from their colleagues in account management as well as highlighting just why account handling is crucial to our business when it is done well. This idea certainly feels reflective of the way that we need to work when selling ideas - especially when facing highly fractured, matrix organisations operating in a range of geographic locations, which is increasingly the case for many of our clients.

The ‘MacGuffin’ as strategic vehicle

The concept of a MacGuffin is attributed to Alfred Hitchcock and defined as “an object, event or character in a film or story that serves to set and keep a plot in motion despite usual lacking intrinsic appeal”. There are many famous examples of this narrative device, most salient for me is the briefcase in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction.

Hill references the use of a MacGuffin as a strategic device through the example of Low2No , a Low Carbon building project in Finland. Hill notes that there are loads of great intellectual concepts in his industry that, despite huge amounts of money being spent on their development, have gone nowhere. Ideas around more sustainable building materials or ‘smart cities’ fail to take hold “not (because) it’s a bad idea; it’s just there is not enough motivation to make (them) happen… it’s missing a macguffin” (Hill, p.54). In the case of Low2No, the building represents not just a physical artefact/product but the platform for innovation and initiatives delivered via “a wider series of strategies, all of which are harnessed through the gravitational pull of the building itself” (Hill). The project he references was crucial in changing planning restrictions around the use of timber in commercial building, paving the way for more sustainable approaches to construction in the future. If these changes had been proposed outside of the context of the specific building, they would not have been permitted.

This device made me think about the number of ‘good ideas’ that don’t go anywhere - and why this happens. As with the example above, it’s often because of a lack of will or momentum rather than a criticism of the thinking itself. So, the question becomes how can we use the briefs where there is momentum and energy as a vehicle to drive forward initiatives and ideas that might ordinarily not have happened?

Ideas as a Trojan Horse

Hill then offers a small twist on this idea. Alongside a MacGuffin, he proposes how projects can be used as Trojan Horses, which he describes as “an artefact with hidden strategic elements” (Hill, p.58). Using the Low2No project once more as a reference he suggests that whilst the output of this work is fully functioning building it is also an opportunity to question “how to use procurement more effectively… how to rethink food culture in Finland… how to provide a future for the Finnish timber industry…how to explore carbon accounting…” (Hill). The project is “a carrier of multiple strategic outcomes well outside of a traditional building. With the emphasis on replicability, each outcome is in effect a platoon pouring out of the Trojan Horse and marching across Finland”(Hill, p.61).

Conceived on in this way, the projects we work on represent not just the opportunity to produce a ‘physical artefact’ (or a campaign, advert etc) but to explore other questions which will inform the way we work in the future. Questions which we can establish as part of a repeatable model, deploying the tools and techniques across other client work. So often we think about projects - in pitches especially - as an opportunity to demonstrate what we already have. A more powerful question could therefore be, what do we want to do in the future? And how do the projects we’re faced with give us the opportunity to build this capability.

Building multi-speed strategy

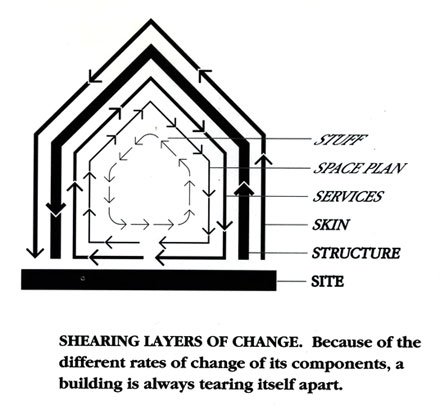

Drawing from Stewart Brand’s book How Buildings Learn, Hill discusses how institutions are made up of various layers of activity, with each layer working at a different speed. According to Hill, “Brand sees structures comprising different layers that shear against each other at different paces and sees an adaptive structure as one that enables ‘slippage’ between differently paces systems, such that a structure ‘learns’ and improves over time” (Hill, p.72). To visualise this, Brand created the Shearing Layers model, below:

Brand’s model breaks down the component parts of a building, from inside to the out. He expands this model by defining the temporal component to each layer. The site for example, is in theory, permanent. In contrast to this is ‘the stuff’, which lives inside the building, and change on a daily basis. Developing this further, Brand came up the idea of pace layers, a concept which moves away from the physical buildings themselves, but addresses exterior, cultural and contextual factors and the speed at which they moved.

The work of Binet and Field has popularised an appreciation of the temporal component to advertising and communication effort - we now think about activity regularly through the lens of long and short term payback . But, there is a tendency toward seeing only the long term as ‘strategic’, with short term activity being more tactical in nature.

Brand’s Shearing layers model feels like a useful means of thinking about brand architecture and experience and transferring a model for thinking about the architecture of buildings to the architecture of brands feels somewhat appropriate. This model enables us to ask ourselves how the various ideas, touchpoints and assets which constitute how a brand shows up in the world of the consumer manifest themselves. It allows us to conceptualise how frequently the components of a brand’s need to be changed, modified or updated, if at all. We can think about the way the whole brand is experienced and work with the different component parts according to their own strengths and characteristics, rather than treating each component in a singular way.

Pace Layering meanwhile, provide a useful lens through which we can think about the specific qualities of different types of media and communication and how they are consumed by audiences. How do the different channels and messages we’re deploying work together in the communications plan? How are we delivering our long term, ‘slow’ moving messaging and how does this correspond to our ‘fast’ media and messaging choices? Are the components of your plan balanced or biased disproportionately to a specific ‘speed’? Do your choices meet the needs of the brief?

These models provide a useful reminder that good strategy encompasses both ‘fast’ and slow choices - the key issue is one of co-ordination and balance. In a world that requires and encourages ‘systems thinking’ more and more, this kind of devise is a useful addition to the armoury of frameworks through which a communications planner can ply their trade (Incidentally, Martin Weigel’s brilliant dissection of the concepts of culture and fame also references these models to good effect).

Questions > Problems

“Cedric Price told a story of prospective clients, a husband and wife, coming round to discuss the new home they wanted him to design. Price sat through the dinner, listening to the to-and-fro between the couple with some discomfort, before pronouncing: “My dears, the last thing you need is a house, you need a divorce” (Hill, p.127)

A large portion of Hill’s thesis deals with what he sees as the main challenge facing designers today. He makes the case that all too often designers and their product are utilised by their clients/customers at the wrong time and in a way which limits the potential impact they can make. “Design has too often been deployed at the low value end of the product spectrum, putting lipstick on a pig…design has failed to make the case for it’s core value, which is addressing meaningful, genuinely knotty problems by convincingly articulating and delivering alternative ways of being. Rethinking the pig altogether, rather than worrying about the shade of lipstick” (Hill, p.30).

The same issue faces strategists in the communication business too. I loved the thought about ‘articulating and delivering alternate ways of being’. It is redolent of Stephen King’s planning cycle and the question it asks its user: Where are we, where could we be and how are we going to get there? Strategy is a creative discipline. It is a discipline which needs to imagine and articulate alternate ways of being and a create a cohesive plan for getting there. King’s work to create the Mr Kipling brand for RHM is a supreme example of this vision in practice.

What has happened in the 55 years since King brought Mr Kipling into the world is that the purview of our work has narrowed. Agencies have gone from spanning the entirety of ‘the 4Ps’ to specialising in one of them. Our industry has fragmented. Strategy no-longer lives in one place, but many. We have a creative strategy, a media strategy, a social strategy, a CRM strategy, a programmatic strategy, a search strategy and so on and so on.

We like to talk about the power of problems - and how defining and reframing the problem faced by our clients is central to unlocking better quality work but, as Hill notes “the consultancy model does not have the necessary freedom to radically change the brief, to work the context and search for radical solutions outside of it’s engagement” (Hill, p.126). To refer back to the quote at the beginning of this section - could an architect legitimately recommend a divorce having been approached to design a house? I have lost count of the number of times I have been asked for a media plan when it was plainly obvious that merely advertising would not rescue the fortunes of the product or service at the heart of the brief.

Hill’s provocation is that a focus on problems is part of the issue. Instead, we need to find ways to inform and develop the questions asked of us by our clients - to start to inform the places and spaces in the process where we’re able to play, which in turn will allow us to better, more impactful work that is both coherent and effective in today’s commercial landscape. A focus on questions, not problems is the unlock to this. As is so often the case, it comes back to a discussion of outcomes vs. outputs and how we move to a position where we can trade in work which delivers the best outcome for a client rather than delivering a pre-determined output.

As the responsibility for marketing and brand management moves away from being solely the responsibility of the marketing department (who themselves are becoming specialised into one of the P’s as well) agencies need to work to build relationship and influence beyond the walls of the marketing department rather than being stuck at the “lipstick end of the pig”, a position from you often can’t genuinely solve problems, only “try harder” within the context of the brief you’ve been set (Hill, p.35). Good clients enable this, providing the connective tissue for agency teams to branch out and start to explore the organisation beyond the core marketing function.

A Strategic Vocabulary

It was interesting to read a book about strategy as it is practiced in an industry outside of my own. To understand how people approach their work, but also to observe that many of the problems we’re dealing with in communications regarding the influence and impact of strategic thinking are being shared by other creative disciplines too. Hill’s attempt to create a vocabulary via the frameworks, devices and observations above help add order to a world which we will all identify with. A world that is complex, volatile and uncertain. Attempting to create shared understanding via a common vocabulary focussed on the issues at hand is something every strategist can appreciate. After all, sometimes our words are all we have.

Bibliography

Hill, D. (2012). Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary. Moscow: Strelka Press.